The Dragon and the Pachyderm

Pakistan is in dire straits, literally and figuratively. Things didn’t always go well for Islamabad and they haven’t been well for a long time. Pakistan has been in the middle of some quite unstable regions of the world but it has also itself to blame for much of that instability and tension.

The concept of Pakistan is one of the strangest to come out of the decolonization process. Like many African failed states Pakistan is not a nation; never to have existed before, never to have fought before, its citizens patriotism grounded on religion and geopolitics alone. This is not a good recipe for success and Pakistan’s shameful economic underperformance when compared to other emerging nations is proof. If true that many new states such as Canada or Australia thrive in spite of their weak national identity and historical precedent, it is also true that states such as these are more the exception than the rule. Pakistan like many African or Latin American countries, is devoid of any collective memory or administrative tradition that can hold the state together in times of need. Everything about Pakistan seems the product of arbitrariness: from the shape of its borders, the location of its capital, the composition of its people, the form of its government or the very name of the country. Nothing was organically constructed, all of the country’s features having been decided on the negotiating table and implemented top-down in a megalomaniac social engineering endeavour. The economic performance of Australia and Canada is mostly due to small populations living in wide resource rich territories and an ethnic population largely made up of protestant Europeans with their productive mentality. Pakistan is the paradigmatic example of the planet’s general opposite, a weberian insult in name as well as in essence.

After so many decades of political instability and military defeats, Pakistan won’t disaggregate now, but the light national coherence that Islam, the military establishment and Pakistan’s geopolitical allies provide, can only help it to a certain extent. Many analysts of Yugoslavia would look at Pakistan and call it a disaster waiting to happen. The past few years, one must admit, have been particularly strenuous. America’s tensions with the Islamic world have exposed Pakistan’s inclinations for the sponsoring of terrorism bringing it the contempt of the international community, India’s economic success has left its inferiority complex and Indophobia even more exacerbated, NATO’s campaign in Afghanistan has destabilised the Northwest Frontier Province and brought a home grown insurgency to but a few kilometres from Islamabad, Pakistan’s Afghani strategic depth is all but lost, India backed or otherwise Baluchistan is momentarily rebellious, America’s and Europe’s rapprochement with democratic India has relatively deprived Pakistan of western FDI and reliable sources of technology, the international community’s lobby for a democratic government has given Pakistan a weak and unstable leadership and last but not least the massive floods will demand massive investment, will cause widespread popular discontent and will require decades to recover from.

It is against this backdrop that we must put emerging China at play.

The Indian Ocean rim is the home to what strategists call the shatter-belt: a region of juxtaposed political, economic and strategic interests which a shifting world order is yet to balance. The flow of Persian Gulf oil to the East through the Indonesian straits, to the west through the Red Sea, the regional power politics in the Indian subcontinent, in Eastern Africa, in Indonesia, in the Indochina peninsula and of course, the interests of the external powers. Historically the Indian Ocean rim was never dominated by local powers for the continental character of these polities always made sure that the strategic emphasis was on land disputes and not naval ones. We can thus explain the Arab trade routes stemming from the Arabian Sea, the Ming dynasty’s influence projection armadas and the European colonial empires in modernity. What local naval power there was, was largely confined to coastal rivalries. Then and now, capable fleets are to be found in the Ocean’s northern and north-eastern rims – Australia’s and South Africa’s capabilities being a historical oddity. Indonesia’s big fleet is always poised to act in its own territory being tasked to prevent any insular uprisings. It must also serve as a centripetal counter-weight to regional rivals Malaysia and Australia as well as any potential external force. Africa cannot sustain a naval military establishment and the Middle Eastern states always use their navies with their own regional concerns in mind. This leaves Delhi and Islamabad as the only naval forces prone to project power in the Indian Ocean rim. But Pakistan’s troubles make it unlikely that it will dare challenge India’s primacy any time soon.

Conceivably, only China can now help preserve an anti-India orbit within the Ocean. In addition, there are several indicators that point to a possible Chinese naval deployment in the near future. First and foremost, China is in the process of finishing the infrastructure that will allow it to keep the Indian Ocean from becoming an Indian lake. Facilities in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Pakistan and perhaps even in Sri Lanka along with plentiful goodwill towards China make sure that Beijing’s vessels can soon be welcomed. China’s recrudescing assertiveness in the South China Sea demonstrates that Beijing is leaving its non interventionist stance, to take a more active role in Asian affairs.

The issue of China’s economic growth is also an important factor since it is not guaranteed that this growth can continue indefinitely. In the case of a slowdown or the bursting of a financial bubble for instance, the Chinese government may face heavy domestic criticism. In this scenario, the more accommodating Chinese foreign policy pundits might find it hard to argue in favour of interdependence and lose ground to the more belligerent pundits – mostly voices within the Chinese military establishment – which favour a hard power approach. In the last few months these voices have been stronger than usual. As has been observed in the past, as far as Beijing is concerned domestic opinion counts more than any other. It is not impossible that the Chinese leadership might put strategic issues in the agenda in order to minimise the popularity loss deriving from economic malaise and in this case Beijing would naturally prefer a smaller challenge like India than the big challenge of the American and Japanese control of the ‘first island chain’ and Taiwan.

In modern times the only external powers to have attempted and failed at projecting power into the Indian Ocean were Japan and the USSR. During World War II Japan was able to go as far as to bomb Darwin and to attack India and Sri Lanka with a carrier task force in the Andaman Sea. The USSR kept a squadron of the Pacific Fleet in the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb with logistical help from local client states and the Vietnamese base of Cam Ranh Bay. Japan failed because it couldn’t hold off the US Navy while keeping the war going in the west and because it had virtually no allies in the rim. The USSR failed because its supply lines were too long and the American presence too strong for its naval force to have a significant impact. China does not ail from these predicaments: its allies are numerous, the US Navy is otherwise distracted with the Middle East as well as in process of downsizing its assets and India’s navy is not as pervasive as to not be checked by a Chinese rival presence.

Hence the future of a Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean may be closer than expected and the first glimpse the world had with the deployment of a frigate task force to the Somali waters in an anti-piracy mission may be the prelude to something more ‘significant’.

Tales from the Shia Crescent

Halford McKinder seems to be quite popular in both Tehran and Damascus these days. Several reports have recently emerged about a new strategy developing in the shia governments which consists of an alliance with Russia and Turkey – which implies autonomy from and circumvention of the West – in order to secure a new geopolitical order.

This alliance would permit the ‘heartland’ powers not to rely on sea lanes and control the pipelines which flow through Eurasia. By supplying Europe and China through land, more dangerous and hostile routes through the sea could thus be avoided and allow the four allies unfettered influence in Central Asia and the Middle East.

Allegedly, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has been active in the promotion of what he designates as the ‘Four Seas Strategy’, a plan to unite the energetic future of the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean and their respective pipeline networks under the quadrilateral leadership of Moscow, Ankara, Tehran and of course Damascus.

In the Mediterranean, the natural gas to be found off the Levantine coast as well as the oil tankers coming out of the Suez would thus be diverted to the Syrian and Turkish coastal pipeline hubs and carried expediently to the Balkans and central Europe using preferably the South Stream network. In the Black Sea, Turkey and Russia would control the oil flowing through the Baku-Tbilisi pipeline and the trans-Caucasian infrastructure and secure the supply of Central Asian oil and gas to Europe. The Caspian Sea would be protected by the Russo-Iranian tandem which would ensure the eastwards flow of Iranian, Caspian and Central Asian fossil fuels to China and India. Finally the Persian Gulf would form the final source of oil reserves to be expediently supplied through Iran to Turkish and Russian pipelines as well as to the Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline.

Turkey is the naval hegemon of the eastern Mediterranean and with Russia considerably reinforcing its Black Sea fleet with Mistral class vessels and the refurbishing of the Tartus naval installations in Syria for use of the Russian Fleet’s 5th squadron, any potential rivals of Moscow or Ankara would feel dissuaded from intervention.

If ever this vision came into being, such an alliance would top all geopolitical arrangements on the planet: bearing more military might than OPEC, more energetically autonomous than NATO. Extending throughout the Russian steppes, the Anatolian valleys and the Iranian mountains hardly could any external entity threaten the use of force.

The basic idea is to replicate the past forte of the Muslim world: intermediacy. By controlling the trade routes, this ‘heartland bloc’ would rival, and keep at bay, any and all external superpowers: America by containment, China and India by co-option.

But the very fact that such a pact would wield insurmountable strength should hint at the unlikelihood of its inception; like many such concepts, if it sounds too good be true, it usually is.

An alliance should always be based on objective interests but the most enduring alliances are the ones that include normative bonds. While NATO was formed against the Soviet threat, the Atlantic philosophical links helped its maintenance throughout and even after the Cold War. The same can be said of the Treaty of Windsor or the Saudi-Pakistani alliance.

‘This is the safe rule – to stand up to one’s equals,

to behave with deference towards one’s superiors,

and to treat one’s inferiors with moderation‘.

– History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides

This proposition however ignores any such links beyond a desire for autonomy from the Washington Consensus. Iran, Turkey and Russia are roughly equivalent in power and historical rivals competing for the same areas of influence. Only an extremely powerful threat would bring such rivals together; the USSR, a universalist superpower and successor state to the old Russian Empire was such a threat and caused Tehran and Ankara to join efforts in its containment. The US however are not. American influence in the Caucasus and Central Asia is not unilateral and in many cases relies on regional interlocutors such as Turkey and Russia – lest we forget their bases’ availability to the USAF. While the American navy keeps naval supremacy in all oceans and seas, Washington’s power is waning and Secretary Gates is conducting massive expenditure cuts which will on the medium term imply compromises in the global naval hegemony of the US Navy. Given this state of affairs Russia and Turkey have no need to affront the remaining superpower for they possess enough leverage as it is. Not to even mention that Russia would hardly consent to dependency on Islam.

The al-Assad plan seems ultimately to be wishful thinking. If for no other reason the notion has been advertised by Damascus and Tehran but has had little resonance in more ambiguous Ankara and Moscow.

The shias’ fundamental errors? Anti-Americanism – the nature of Iran’s regime is not a major hindrance for cooperation with the US, blind hostility towards America is – and ignorance of the dynamics of multipolarism.

Leone, Volpe …e Aquila

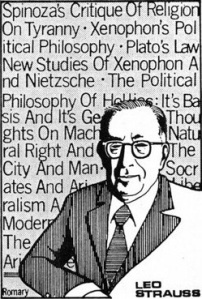

It seems to be a common misconception that Leo Strauss inspired himself in Niccolo Machiaveli. In my view, that his thesis were influenced by the Florentine secretary is quite clear and Strauss himself wrote abundantly on Machiavelli but it is a misconception that neo-conservatism derives from the Machiavellian school.

It seems to be a common misconception that Leo Strauss inspired himself in Niccolo Machiaveli. In my view, that his thesis were influenced by the Florentine secretary is quite clear and Strauss himself wrote abundantly on Machiavelli but it is a misconception that neo-conservatism derives from the Machiavellian school.

There are many who enjoy writing on the similarities between the two, on when and how the American’s ideas were shaped by those of the Florentine. Regrettably, scholars and researchers seldom take the time to consider what sets them apart. There are even those who go as far as to have difficulty in setting them apart, not trying to hide an ill-considered admiration for both…

First and foremost the academia might like to start with the moral considerations Leo Strauss made of Machiavelli. The secretary was often complemented in Strauss’s work for his brilliance and revolutionary ideas, for the pioneering rationale of his thought. That being said, Machiavelli’s groundbreaking thought aside, Strauss often used the Machiavellian school to mark a contrast with the proposed theories which he himself advocated.

For Strauss after all, Machiavelli represented the foundation of the very philosophical forces which neoconservatism was being conceived to fight. Machiavellian ethics had been insidiously crucial to the separation of Church and State, to the advent of liberalism but the Machiavellian teachings also marked the original sin of the liberal school in so far as it carried with it the nihilist gene for Nietzschean social disintegration.

This alone ought to give pause for those who are too eager to precipitously establish the analogy between the two thinkers. However, there are other aspects. One in particular will be addressed, for in today’s post-modern societies it is one of the most controversial: deception.

I assert that Leo Strauss reified the term.

Many neocons are not religious but in spite of this they are prominent thinkers of the GOP and the religious right, in America. The reason for this is the straussian belief in the need for Machiavellian methods in the triumph of good against evil. For the neoconservatives, society is to be a consensus of morality since only morality can check the inherently subversive forces of liberalism. Social morality therefore is a necessary fiction meant to preserve society as a cohesive compact; and the neoconservative pundits are thus comfortable in their respective advisory roles.

This logic however perverts the Machiavellian rationale and it does so in two different ways: on one hand it applies to society, precepts advised for the political leadership, on the other hand it mistakes ends with means.

‘Il Principe’ was meant for a statesman, it taught the natural need for pragmatism and cold calculism in politics but Strauss’s interpretation of Machiavellian deception is erroneous in its assumption that deception can be equated to myth. Both imply deceit but only the latter can be messianic. Strauss as an American naturally tends to understand deception as a mechanism for condescending fiction, a natural emulation of the Founding Fathers’ legacy. This is dangerous and it reveals the bias of a national of an ideological empire. Only a national of a new country which has known but one guiding regime ideology can misunderstand the teachings of a renaissance sceptic ideologue, only he can interpret a historically empirical observation as an instrument for the service of a specific normative doctrine. The danger comes from the inherent potential for social engineering. Machiavelli was not writing a utopia, he was not prescribing the parameters for the perfect society – he was advising a political leader not a social worker.

For Machiavelli attitudes such as cruelty or charisma are nothing but instruments for the wielding of power:

‘A wise prince will seek means by which his subjects will always and in every possible condition of things have need of his government and then they will always be faithful to him’.

For Strauss these attitudes are not supposed to serve the leader or the state but rather the contemporary and not yet corrupted form of liberal society.

In Strauss, Machiavelli’s means – justified by the ends – are instead ends in themselves. The straussian deception is the fiction of the moral society. This fiction/deception/myth is both the means and the end of the urgent preservation of liberalism from its nihilistic tendencies. Straussian doctrine exists as chronological exception whereas Machiavellian doctrine exists as historical normality. The former is based on a linear perspective of history with democratic liberalism at the top of human socio-political evolution, the latter is based on an empirical and circular vision of history where human behaviour is by and large a constant.

On the necessary qualities to feign for the benefit of the masses, the Prince is advised by Machiavelli to primarily feign piety and morality. Of course it is one thing to keep the masses convinced of their leader’s moral superiority, it is another altogether to transform the masses themselves into an amorphous morally compliant throng.

The New Zealand Analogy

Aaron Ellis over at Thinking Strategically was particularly distraught at Melanie Phillips’ passionate condemnation of the Cameron government’s policy in regards to Israel. Phillips in her neoconist tone, attacked the Conservative-LibDem government for its forsaking of democracy ideals to the benefit of cheap financial motivations. Phillips is mostly concerned with London’s enabling of an ‘islamist’ government in Ankara, one which has recently caused a number unnecessary spats with Israel.

This blog has been quite keen in pointing out that Turkey’s current approach to Israel has ulterior motivations which are not strictly in its best interest and in that sense one can understand Melanie Phillips criticism of Turkey. The lady at The Spectator however goes too far when advocating a distancing of Britain from Turkey because of Israel.

Ellis’ post makes a fine case in pointing out that:

Indeed Phillips’ moral reasoning would be much more fitting for a Church pulpit rather than a political magazine and her criticism of Cameron’s ignorance of foreign policy matters makes the term ‘projection’ come to mind.

Nevertheless there is danger in leaving the rational apology of Israel as a monopoly of the Neoconservative persuasion.

Ellis seems to subscribe the Mearsheimer-Walt thesis of the ‘Israel Lobby‘: Israel’s importance to the west is purely symbolic and its defence by western governments is based more on cultural sympathy rather than hard national interest. Walt and Mearsheimer go as far as to say that for America, the staunch defence of Israel has actually hurt US national interest in so far as it undermined the United States’ power-broking credentials in the Middle East and caused irreparable damage to the Arab-Israeli Peace Process.

Admittedly the other side of the debate on Israel has not been the most articulated but strategy cannot exclusively rely on crude economic cost-benefit ratio analysis. Berlin after the second great war was a pile of rubble and yet the Allied powers were quite adamant in retaining it as a shared capital, going even as far as to risk war over it.

Israel, while an economic powerhouse when proportionately compared to its neighbours, is not indispensable to most European states. Strategically speaking the European capitals capable of projecting power have since long turned towards an ‘Arab policy’ which is much more able to guarantee UN votes, far reaching markets and oil.

The neocons’ obsession with Israel pertains to its regime – a liberal democracy – and its location in the Middle East. For the PNAC progeny, Israel is both a sacred paradise of liberty for the west’s moral imperative to zealously guard and the gateway for the transformation of the Greater Middle East. Israel proves the power of liberal institutionalism in shaping society and intends to purge the Arab world from illiberal traditions through compassionate western social engineering.

Therefore Aaron Ellis is right when claiming that ‘At the core of the [Melanie Phillips’] piece is the belief that Islamism poses a mortal challenge to Britain and that Israel is more important to us than Turkey. This is dubious‘. Yet I contest that it is of zero strategic value and more to the point I sustain that it bears considerable strategic importance, at least to US foreign policy.

Relations between states can assume a wide range of forms and are quite diverse in nature. Strategic allies cannot be recognised by bilateral trade relations – although free trade agreements transmit deep political confidence – nor through simple military cooperation. Throughout the Cold War the US and the SU held large networks of military client-states which were of little or no strategic value, and France and Germany continued statistically great commercial partners in spite of their clashes during the XIX and XX centuries.

It is technology and intelligence sharing that more accurately give away the intentions of a state and its foreign policy. An example in point of fact is that of the significance of New Zealand for the US and the Anglosphere. New Zealand is a successful democracy and economy but a superpower like the US would always have little use for a couple of sheep grazing islands in the antipodes. How then to explain America’s Britain’s and Canada’s excellent relations with Wellington? Surely Indonesia would hold more strategic and economic value for the aforementioned industrial powers…

New Zealand is part of the Echelon network and enjoys access to the best American military technology. This makes it one of America’s closest allies on the planet. This proximity however is not anchored on strategic location or economic interest but rather on cultural harmony. New Zealand is a liberal democracy, but it is a WASP one as well. The national narrative is highly compatible with that of America.

Strategic value must rely on national interest but it is all the deeper, the closest the cultural relations are between the states in question. Unlike the neocons I will not recur to the ideology or the nature of the regime but more importantly to the nature of the state. Israel is and will remain important to the US not because of its regime but because of its national narrative: that of an anti-British imperialism, religious persecuted minority and immigrant founded nation with a strong Judaeo-Christian messianic discourse.

The strategic value of Israel in my view, lies in being the most culturally compatible state with the US in the Middle East. It is not democratic peace theory which is at stake but national identity – not simply ‘friendship’ as Ellis put it. This factors in strategy when it comes to the durability of strategic bonds. Egypt would be more useful no doubt but also more fickle for who’s to say that a coup in Cairo tomorrow, won’t turn the entire country against Washington? It happened before in Iran where the entire Iranian military establishment was put to use against American interests, where Washington’s intelligence gathering infrastructure against the USSR had to be evacuated and where not even its embassy was spared.

In spite of occasional conflicting interests, diplomatic snubs and mutual espionage, Israeli links to America are likely to remain strong and it is this proximity which makes Israel a suitable base for American operations in the Middle East in decades to come. The same cannot be said of the Arab regimes or the other regional powers.

Unlike Walt and Mearsheimer I reckon the links between Washington and Jerusalem to not be exaggerated. Israel will never integrate the Anglosphere and indeed the US does not provide Israel with all it would like to acquire in terms of technology or intelligence – Jerusalem argued against invading Iraq and was rebuffed, appealed to a US strike on Syria in Al-Kabir and Bush refused, as he did Israel’s request for further bunker piercing weaponry or the transponder codes to overfly US controlled Iraq en route to Iran – but Israel’s appeal to Americans will always be great and perhaps even greater than that of many NATO states, and that is a sound anchor for bilateral relations in such a hostile region as the Middle East.