REALISTS Vs IDEALISTS

The Neocons vs. The Realists

A must-read debate about our foreign-policy future. Does realism offer the best solutions to today’s threats? Or will neoconservatism be responsible for our policy triumphs? The choice is clear after eight years of failed Bush policies, says Walt, but Muravchik thinks the House of Kristol may well be vindicated.

The Future is Neocon

Joshua Muravchik

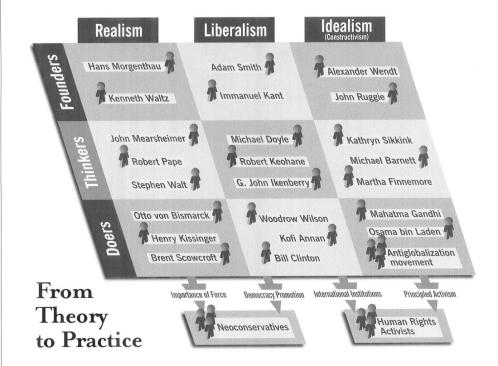

TO COMPARE the records of realism and neoconservatism we must first define our terms. Realism consists of two mutually contradictory propositions. One holds that states are bound to behave according to their innate interests. Thus, Hans Morgenthau argued that politics is “governed by objective laws” whose “operation [is] impervious to our preferences.” The other holds that states may deviate from their interests but ought not do so. Thus, George Kennan argued that “the most serious fault” in U.S. foreign policy was the tendency to take a “legalistic-moralistic approach to international problems.” Without resolving the inconsistency we may stipulate that realism posits that states do or should hew closely to a tight conception of the national interest, revolving around matters of geography, resources and power.

Neoconservatives were originally a circle of writers who proclaimed no “ism.” Their approach to foreign policy consisted of what Max Boot has called “hard Wilsonianism.” As one such neocon, I would stipulate that the essential tenets, in contradistinction to realism, include giving a greater weight to moral considerations, attributing larger importance to the ideological element of politics and above all favoring a more contingent assessment of the national interest. While realists believe that we will be safer by seeking to avoid unnecessary broils, neocons believe that we will find more safety using our power to try to fashion a more benign world order. On these points, neocons are liberal internationalists. Where they part company from liberals is in a greater readiness to resort to force and a lesser appreciation of the United Nations. (Realists think little better of the UN, and neither are most of them squeamish about using force, but since they define U.S. interests so narrowly, they see fewer occasions for it.)

U.S. policy has rarely mirrored one school or another in perfect reflection. Policy ordinarily flows from a confluence of sources, including some—for example, domestic politics—that have nothing to do with strategy or philosophy. Nonetheless, it is relatively easy to identify policies that have been more influenced by one school than another.

HOW HAS the United States fared when policy hewed closely to the realist or the neocon approaches?

The most important points of comparison are the respective aftermaths of the two world wars. Following the first, the United States spurned Wilson’s architecture of peace and turned instead to realism. Realists may claim that the ensuing twenty years, the most catastrophic era of American foreign policy, ought to be charged up to “isolationism” rather than laid at their doorstep. But this would be a semantic dodge. Isolationism is nothing more than realism in an extreme variant. And U.S. policy in the 1920s and 1930s was not strictly isolationist. On the contrary, these years saw the creation of the foreign service, continued activism in the Western Hemisphere, invigoration of the “open door” in the Pacific and repeated efforts to solve Europe’s financial crisis, amidst a general emphasis on the economic side of international life. What were averted were Wilson’s high idealism and the commitment to using American power to preserve the peace. In short, it was an era of realism. And it led directly to the most disastrous event in human history, a war that snuffed out some 60 million lives, including more Americans than have died in all of our other foreign wars combined.

After the Second World War, in contrast, America turned to what we would today recognize as a “neocon” approach. By this I mean that we set out on the most globalist path that any noncolonialist power has ever undertaken. We formed alliances in Europe, Northeast and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and the antipodes; girdled the globe with military bases; fostered international institutions that helped restore the world economy and gave away an impressive fraction of our income in foreign aid. Above all, we proclaimed a strategy that defined the entire world as the arena in which we would confront our new adversary. This insistence that our own security was linked to the security of others in every corner of the world was the very antithesis of “realism.” Senator Robert Taft bemoaned that we were acting as “demigod and Santa Claus to solve the problems of the world.”

At the time, these policies were termed “liberal internationalist”; the term “neocon” had yet to be coined. But they were muscular policies (we were spending roughly 10 percent of our GNP on defense), to which today’s neoconservatism is the heir much more than today’s liberalism. While realist policy following the First World War led to unparalleled disaster, neocon policies after the second achieved what was arguably the most perfect success in the history of statecraft—our relatively bloodless victory over a foe possessing the most ponderous military machine ever assembled.

Of course, containment was not a perfect strategy. It led to woe in Vietnam. And, too, realists made their contributions to containment, notably the anti-Soviet alliance Henry Kissinger forged with Communist China. But the overall strategy was of neocon design, and it was brought to successful conclusion by the arch-neocon, Ronald Reagan. He rhetorically challenged the “evil empire”; fostered guerrilla war against Communist regimes in godforsaken places; promoted universal democracy; and undermined mutually assured destruction by means of “Star Wars.” These successful tactics were decried by realists as reckless diversions, just as they were cheered at every turn by neocons. Indeed, neocons helped to shape them. Jeane Kirkpatrick was one of their principal intellectual architects. Richard Perle steered the administration’s nuclear-weapons policies. Elliott Abrams was the point man for the “Reagan Doctrine,” which itself was formulated not by Reagan but by neocon columnist Charles Krauthammer.

The Soviet Union presented a challenge—partly conventional military, partly unconventional military and above all ideological—for which realism was not designed and to which it had no answers.

NOW, WHAT about the post-cold-war world?

The first challenge was Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. The path to this event was paved by one of America’s most nakedly realist sallies, our quiet support for Iraq in its war with Iran in the 1980s. This is reported to have included sharing intelligence and funneling arms from third countries, as well as averting our gaze from Iraq’s use of chemical weapons. Had it not been for this support, Saddam Hussein might have been in no position to make a grab for Kuwait in 1990, nor perhaps would he have assumed American acquiescence. This assumption was reinforced by the assurances offered by our ambassador, April Glaspie, that the United States does not intervene in intra-Arab quarrels. Whether she was to blame for this much-criticized message or was merely following orders, it undeniably represented a realist sentiment.

The first challenge was Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. The path to this event was paved by one of America’s most nakedly realist sallies, our quiet support for Iraq in its war with Iran in the 1980s. This is reported to have included sharing intelligence and funneling arms from third countries, as well as averting our gaze from Iraq’s use of chemical weapons. Had it not been for this support, Saddam Hussein might have been in no position to make a grab for Kuwait in 1990, nor perhaps would he have assumed American acquiescence. This assumption was reinforced by the assurances offered by our ambassador, April Glaspie, that the United States does not intervene in intra-Arab quarrels. Whether she was to blame for this much-criticized message or was merely following orders, it undeniably represented a realist sentiment.

The decision to force Iraq to disgorge its prey was taken by a realist president surrounded by realist advisors like James Baker, Brent Scowcroft and Colin Powell. But this necessary action received more solid backing from neocons than from other realists, some of whom, such as Patrick Buchanan, Zbigniew Brzezinski, James Schlesinger, Russell Kirk, and columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, among others, echoed most liberals in opposition to the war.

The war concluded on a consummately realist note—the decision to leave Saddam in power. The principal justification given for not marching on Baghdad to oust the dictator ourselves was that this would exceed the UN mandate under which we were fighting. But this does not explain our response to the large insurrection against Saddam that broke out at war’s end. Although we had ordered the grounding of all Iraqi military aircraft, we allowed an exception for the helicopters used against the rebels, and when Saddam’s loyal Republican Guard battalions passed close to American lines on their way to suppress the uprising, we made no effort to hinder them. Neither keeping those choppers grounded nor scaring off Saddam’s troops would have violated any mandate or involved us in more fighting. So another reason must be found for our cynical complicity in Saddam’s retention of power. In a joint essay some years later, former-President George H. W. Bush and former–National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft claimed that they did in fact want Saddam removed from power, but they also offered an insight into the realist calculations that led them to act otherwise. “Neither the U.S. nor the countries of the region wished to see the breakup of the Iraqi state,” they wrote. “We were concerned about the long-term balance of power at the head of the Gulf.”

BY THE mid-1990s we found ourselves faced with a series of local bloodlettings that raised humanitarian concerns more than ones of security. In general, neocons would treat purely moral concerns, such as human rights, as a higher priority than would realists. In the episodes in question, the specific issue was whether America should use force in situations in which the stakes were more moral than strategic in nature.

In the 1870s, Bismarck had summed up the realist position when he commented that stemming mayhem in the Balkans was “not worth the healthy bones of a single Pomeranian musketeer.” To be sure, most American realists today would offer disaster relief to save foreign lives, but they would draw a sharp line against risking American lives to rescue others. The neocon position is a bit harder to distill. Most neocons would endorse military action for purely humanitarian reasons in some circumstances. Where and when would depend on some intuitive arithmetic about how many foreign lives might be saved and how many American lives might be lost in the process.

One hundred and twenty years after Bismarck’s pithy remark though, the Balkans were yet again aflame. The Bush administration brushed this aside with Secretary James Baker’s realist observation that “we have no dog in that fight.” President Clinton continued this hands-off policy, with Secretary Warren Christopher explaining that our inaction amounted to “doing all [we] can consistent with our national interest.”

Realists applauded both administrations for their restraint. Neocons, in contrast, mostly joined the camp urging U.S. action in the form of air attacks against the Serbs and/or supplying arms to the Bosnian Muslims. I and others of my general persuasion—for example, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Richard Perle, Max Kampelman and Charles Fairbanks—argued that in addition to the considerable humanitarian stakes, security considerations also required some form of American intervention. The principle that the United States had advanced in respect to Kuwait—collective response to aggression—was being put to the test. Bosnia-Herzegovina, however fledgling a country, was a UN member recognized by most other states, and it was being subjected to aggression from Serbia. Moreover, it was a European state. Upholding the peace of Europe had been part of the bedrock of U.S. policy since 1945. To tolerate aggression there, neocons believed, would be to invite it elsewhere.

Realists applauded both administrations for their restraint. Neocons, in contrast, mostly joined the camp urging U.S. action in the form of air attacks against the Serbs and/or supplying arms to the Bosnian Muslims. I and others of my general persuasion—for example, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Richard Perle, Max Kampelman and Charles Fairbanks—argued that in addition to the considerable humanitarian stakes, security considerations also required some form of American intervention. The principle that the United States had advanced in respect to Kuwait—collective response to aggression—was being put to the test. Bosnia-Herzegovina, however fledgling a country, was a UN member recognized by most other states, and it was being subjected to aggression from Serbia. Moreover, it was a European state. Upholding the peace of Europe had been part of the bedrock of U.S. policy since 1945. To tolerate aggression there, neocons believed, would be to invite it elsewhere.

The Clinton administration finally brought an end to three and a half years of mayhem after the loss of some two hundred thousand lives, mostly civilian. The action required to bring the slaughter to a halt proved to be extremely modest: a few weeks of aerial bombardment plus some training of Croatian and Muslim forces. This reversal of U.S. policy seems to have been motivated in part by Clinton’s political concerns and in part by worries that the Atlantic alliance’s disarray and impotence was sucking the vital spirit out of NATO. This inference is reinforced by NATO’s subsequent rush to intervene in Kosovo, even though the humanitarian issues were much smaller and the legal basis was nil.

From a neocon perspective, our intervention in Bosnia should have come sooner. Realists, I suppose, regret that we ever intervened.

Unlike Bosnia, where, at least in the eyes of neocons, humanitarian and strategic issues were interlaced, the other most pointed humanitarian episodes of that era, in Somalia and Rwanda, admittedly entailed no strategic dimension. In Somalia, intervention to stanch a famine was undertaken by realists (George H. W. Bush at the urging of Colin Powell), but critics would have a fair point if they said that the action had more in common with the spirit of neoconservatism than of realism. Some half-million Somali lives were in fact rescued, but the episode ended in the deaths of nineteen American soldiers, impelling an abrupt U.S. departure. The moral of this episode, in terms of its implications for our debate, is murky.

Much clearer is the case of Rwanda, where upwards of half a million people were slaughtered on account of their race, the truest case of genocide since Hitler’s annihilation of European Jewry. This massacre was accomplished in mere months, implying a rate of killing even faster than the Nazi death machine. All the while, the United States assiduously refused to lift a finger in response and blocked any UN action in the Security Council for fear it would entail U.S. involvement. Here was a great triumph of realism.

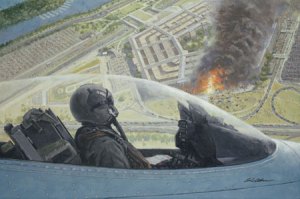

FINALLY, LET us turn to the events of 9/11 and their aftermath. Americans had been murdered by Middle Eastern terrorists on scores of occasions over the preceding thirty years and in ever-larger batches, starting with the murders of U.S. diplomats Cleo Noel Jr. and George Curtis Moore by Black September in Khartoum in 1973, through the bombing of the U.S. embassy and later the Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983, to the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998 and of U.S. military housing in Dhahran in 1996, to the attack on the USS Cole in 2000—among many other bombings, hijackings and assassinations. The 9/11 events constituted a climacteric. Most Americans agreed on the need to go after al-Qaeda. But the evidence that many young Muslims were ready to kill themselves for the pleasure of killing us, and that their deeds enjoyed the sympathy of a substantial minority of their various countrymen, suggested that we needed a deeper strategy, as well.

Liberals argued that terrorists were motivated by misery, and that the solution lay in lifting the world out of poverty. Two things took the force out of this argument. One was the neglect to specify how, exactly, we might achieve the unoriginal goal of universal abundance. The second was that most actual terrorists turned out not to be poor.

Bush, instead, set out to precipitate change in the political culture of the Middle East so that it would breed fewer people ready to commit or endorse terrorism. This was a strategy of unmistakably neocon coloration. Why did Bush, who came of realist stock, embrace it? Because realism had virtually nothing to suggest in the face of terrorism or jihadism.

The closest thing to a realist solution was to break America’s friendship with Israel in the hope of allaying the Muslim world’s anger. To be sure, many Muslims are angry at America’s support for Israel. But the preponderant share of violence in the Middle East does not involve Israel; and the Muslim world’s hatred for Israel is only a symptom of a deeper rage at the West for enjoying a superiority of power and status that Muslims feel rightly belongs to themselves. In short, this solution is as unconvincing as it is unprincipled, and the realists were unable to persuade many Americans of its validity. At a loss to understand why, the least decent of them turned to conspiracy theories.

The war in Iraq grew out of Bush’s neocon strategy, whether or not it was a necessary part of that strategy. Since the war turned into a fiasco, neocons rightly receive much blame, just as they or their ideological predecessors did over the war in Vietnam. But Vietnam was a flawed and painful episode in what proved ultimately to be a sound, even brilliant, strategy. The strategy that led us into Iraq may also in the end be vindicated. Meanwhile, neocons take their lumps for Iraq. But realism remains as barren of answers to the threat of global terrorism as it was to the threat of global Communism.

Joshua Muravchik is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

Stephen M. Walt

TO WHOM should the next president turn for advice on foreign policy: realists or neoconservatives?

Given the disastrous results that neoconservative policies have produced since 2001, the answer seems obvious. Yet despite their repeated failures, prominent neoconservatives are now advising GOP candidate John McCain, and they remain a ubiquitous presence on op-ed pages and TV talk shows and in journals of opinion (along with their close cousins, the liberal interventionists). By contrast, realists have become an endangered species inside the Beltway and a muted voice in contemporary policy debates.

This situation would make sense if neoconservatives had proven to be reliable guides to foreign policy and if realists had been consistently wrong. But the truth is the opposite: neoconservatism has been a road map to disaster while realism’s policy insights remain impressive. If the next president wants to avoid the blunders of the past eight years, he must understand why neoconservatism failed, steer clear of its dubious counsel and rediscover the virtues of realism. To see why, one need only examine the core principles and track record of each perspective.

AS THE LABEL implies, realists believe foreign policy must deal with the world as it really is, instead of relying on wishful thinking or ideological dogmas. Realism sees the international system as a competitive arena where states have to provide security for themselves. Realists know that states get into trouble if they are too trusting, but that problems also arise when states exaggerate external dangers, misjudge priorities or engage in foolish foreign adventures.

Thus, realists keep a keen eye on the balance of power and oppose squandering blood or treasure on needless military buildups or ideological crusades. They know military force is the ultimate guarantor of security, but they recognize that it is also a blunt instrument whose effects are unpredictable. Realists are therefore skeptical of grandiose plans for global social engineering and believe that force should be used only when vital interests are at stake.

Realists appreciate the power of nationalism and understand that other states usually resist outside interference and defend their own interests vigorously. Thus, realists discount the possibility that adversaries will form a tightly unified monolith and favor undermining opponents through “divide and conquer” strategies. Realists also recognize that successful diplomacy requires give-and-take and that the pursuit of U.S. interests sometimes requires cooperating with regimes whose values we find objectionable. In short, realists know that successful statecraft requires strength, cold-eyed calculation, flexibility and a keen sense of the limits of power.

Yet realists are neither moral relativists nor disinterested in values. Realists are aware that all great powers tend to think that spreading their own values will be good for others, and that this sort of hubris can lead even well-intentioned democracies into morally dubious ventures. Realists do cherish America’s democratic traditions and commitment to individual liberty, but they believe these principles are best exported by the force of America’s example and not by military adventures. They also know that prolonged overseas meddling is likely to trigger a hostile backlash abroad and force us to compromise freedoms at home.

HOW WELL has realism performed? The strategy of containment that won the cold war was the brainchild of realists such as George Kennan. Containment focused first and foremost on preventing Moscow from seizing the key centers of industrial power that lay near its borders, while eschewing attempts to “roll back” Communism with military force. Just as Franklin Roosevelt allied with the murderous Joseph Stalin to defeat Nazi Germany, realism dictated that the United States rely on both democratic and nondemocratic allies in the long struggle against Soviet power. Kennan and other realists also recognized that the supposedly “monolithic” Communist bloc actually contained deep tensions, which the United States exploited through its rapprochement with Maoist China in the 1970s.

During the 1960s, realists like Kennan, Walter Lippmann, Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz opposed the escalation of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. They understood that the war was a foolish diversion of American power and that the fear of falling dominos was exaggerated. This view was confirmed when the United States withdrew and Vietnam fought its fellow Communists in China and Kampuchea. Hanoi then distanced itself from its former allies, embraced free markets and normalized relations with Washington.

Realists also understood that the Soviet Union was a Potemkin colossus and that its backward empire was no match for America’s wealthier and more cohesive alliance network. When neoconservatives sounded false alarms about Soviet dominance in the 1970s, realists like Kenneth Waltz correctly argued that the real question was whether Moscow could possibly keep up. Other realists showed that Soviet conventional-military superiority was a myth, and that a Soviet attack against the West was unlikely to occur and even less likely to succeed.1

Neoconservatives greeted the end of the cold war by proclaiming the “end of history” and imagining a long era of benign hegemony, while realists correctly foresaw that it would simply unleash new forms of security competition. When neoconservatives like Edward Luttwak warned that the United States would suffer thousands of casualties in the 1991 Gulf War, realists like Barry Posen of MIT and John Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago wrote articles correctly predicting America’s easy victory. Realists like Zbigniew Brzezinski and Brent Scowcroft also argued that replacing America’s traditional balance-of-power approach in the Persian Gulf with “dual containment” was a strategic blunder that would make it harder to protect U.S. interests in that vital region, a warning that subsequent events have vindicated.2 Although realists recognized that U.S. primacy could have stabilizing effects on great-power relations, they also warned that overly bellicose policies would encourage anti-Americanism around the globe. The past eight years confirmed these forecasts as well.3

Finally, realists were among the most visible opponents of the misadventure in Iraq, and their warnings were strikingly prescient. Neoconservatives were disappointed that the United States did not topple Saddam in 1991, but George H. W. Bush and his main advisor, Brent Scowcroft, correctly judged that ousting Saddam Hussein would

have forced [the United States] to occupy Baghdad, and in effect rule Iraq. The coalition would have instantly collapsed. . . . There was no viable “exit strategy”. . . . Had we gone the invasion route, the United States could conceivably still be an occupying power in a bitterly hostile land.4

In light of what has happened since 2003, their judgment seems sound.

Realists offered similar—and equally sound—warnings before the second Iraq War began. In late September 2002, thirty-three international-security scholars (about half of them prominent realists) published an antiwar ad in the New York Times. It cautioned: “Even if we win easily, we have no plausible exit strategy. Iraq is a deeply divided society that the United States would have to occupy and police for many years to create a viable state.” Other realists wrote articles before the war explaining why it was both unnecessary and unwise.5 On the most consequential foreign-policy decision of the past eight years, realists had the right analysis and offered the best advice.

WHERE REALISTS see a world of states with both competing and intersecting interests, neoconservatives see a stark clash between virtuous, peace-loving democracies and aggressive, evil dictatorships. They imagine enemy forces to be tightly grouped in hostile movements like “international communism,” the “axis of evil” or “Islamofascism” and routinely portray them as a vast and growing danger, even when these forces are in fact deeply divided and their actual capabilities are but a tiny fraction of America’s economic, military and political strength. Nonetheless, neocons argue that it is imperative for the United States to topple this potpourri of minor-league adversaries and convert them into pro-American democracies.

Neoconservatives extol the virtues of American hegemony and believe that other states will welcome U.S. leadership so long as it is exercised decisively. They attribute opposition to American dominance to deep-seated hostility to U.S. values (rather than anger at specific U.S. policies) and believe that enemies can be cowed by forceful demonstrations of American power. Thus, neoconservatives downplay diplomacy and compromise and routinely charge anyone who endorses it with advocating “appeasement.” To the neocons, every adversary is another Adolf Hitler and it is always 1938.

Steadfast support for Israel is a key tenet of neoconservatism, and prominent neoconservatives openly acknowledge this commitment. Most neocons favor the hawkish policies of the Israeli right, and this affinity shapes much of their thinking regarding the Middle East. Specifically, neocons tend to see U.S. and Israeli interests as identical and are convinced that Arabs and Muslims only understand superior force. As a result, they generally oppose diplomatic efforts to resolve regional problems (such as those proposed by the bipartisan Iraq Study Group) and, like hard-line Israelis, tend to favor solutions based on the mailed fist instead.

In short, neoconservatives see military force as a powerful tool for shaping the world in ways that will benefit America, Israel and other democracies. Thus, neoconservatism offers two starkly contrasting visions for U.S. foreign policy: either the United States grasps the sword and uses it to transform the world in America’s image, or it will gradually succumb to a rising tide of aggressive radical forces.

So what happens when the United States bases its foreign policy on this worldview? The answer: nothing good.

NEOCONSERVATISM HAS been around since the 1970s, but its impact on U.S. foreign policy was modest until 2001. Neoconservatives like to portray Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy as epitomizing their ideas, but it was only Reagan’s rhetoric that echoed the neocons’ Manichean worldview. Reagan’s policies were closer to the realist ideal: he lifted the grain embargo on the Soviet Union in 1981, sold advanced weaponry to Saudi Arabia, supported authoritarian states provided they were anti-Communist, withdrew U.S. troops from Lebanon in 1983 when he saw a quagmire looming and sought a balance of power in the Persian Gulf by backing Saddam Hussein’s Iraq against revolutionary Iran. Even the vaunted “Reagan Doctrine” was really just a cost-effective way to pressure Soviet clients rather than a genuine attempt to export democracy. After all, many of the warlords and rebels that Reagan backed (such as the Afghan mujahedeen) were hardly apostles of freedom and liberty.

Reagan’s reaction to glasnost and perestroika departed from neoconservatism too. Wedded to an exaggerated view of Soviet power and convinced that Communist regimes could never change, the neocons were caught flatfooted by Mikhail Gorbachev and among the last to realize that the Soviet Union was unraveling. In fact, leading neocons were deeply disappointed when Reagan stopped condemning the “evil empire” and engaged Moscow in constructive diplomacy. They were equally upset by the realist foreign policy of George H. W. Bush, despite his skillful handling of the Soviet collapse and his wise restraint in the 1991 Gulf War. Thus, reports of neoconservatism’s earlier influence have been greatly exaggerated, and the neocons deserve little or no credit for America’s cold-war victory.

The true test of neoconservatism began after the 9/11 attacks, when it became the intellectual blueprint for U.S. foreign policy. Although there were a handful of realists in the George W. Bush administration, neoconservatives occupied key positions in the Defense Department and in the influential office of Vice President Dick Cheney. Prominent neoconservatives inside the Bush administration included Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, Undersecretary of Defense Douglas Feith, vice-presidential Chief of Staff I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Assistant Secretary of State (and later UN Ambassador) John Bolton, Defense Policy Board chair Richard Perle, as well as aides like Elliott Abrams, John Hannah, David Wurmser, Michael Rubin, Abram Shulsky, Aaron Friedberg and Eric Edelman. Other neoconservatives served as cheerleaders and enablers from their vantage points at theWeekly Standard, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal editorial pages. This situation led Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer to declare that “what neoconservatives have long been advocating is now being articulated and practiced at the highest levels of government . . . it is the maturation of a governing ideology whose time has come.” Similarly, Weekly Standard editor William Kristol proudly proclaimed in 2003 that “our policy . . . is now official. It has become the policy of the U.S. government. . . . History and reality are about to weigh in, and we are inclined simply to let them render their verdict.”

Not since Neville Chamberlain has history delivered such a swift and crushing judgment.

Their chief failure, of course, is Iraq, which columnist Thomas Friedman termed “the war the neoconservatives wanted, the war the neoconservatives marketed.” The neocons were wrong about Iraq’s WMD, wrong about its alleged links to al-Qaeda and above all wrong about what would happen after the United States ousted Saddam. Kenneth Adelman announced the war would be a “cakewalk,” and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz dismissed Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki’s estimates that the occupation would require several hundred thousand troops as “wildly off the mark.” Wolfowitz also told Congress that the war and reconstruction would cost less than $95 billion. Wolfowitz was “off the mark” by just a hair: the price tag for the war already exceeds $500 billion and will probably exceed several trillion by the time we are finished.

Neoconservatives also loudly, naively and wrongly predicted that Saddam’s ouster would yield far-reaching benefits in the region. Fouad Ajami reportedly told Vice President Cheney that the streets in Basra and Baghdad would “erupt in joy the same way the throngs in Kabul greeted the Americans,” and Kristol foresaw a “chain reaction in the Arab world that would be very healthy.” Joshua Muravchik predicted that the invasion “will set off tremors that will help rattle other tyrannies including the mullahs of Iran and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez,” Richard Perle thought Syria and Iran would “get out of the terrorism business,” and Michael Ledeen claimed “it is impossible to imagine that the Iranian people would tolerate tyranny in their own country once freedom has come to Iraq.” None of these rosy scenarios has come to pass.

The most consistent source of dubious forecasts was Kristol himself, who predicted the occupation would require only seventy-five thousand troops and that U.S. forces “could probably be drawn down to several thousand soldiers after a year or two.” On the eve of the invasion, he reassured readers that “very few wars in American history were better prepared or more thoroughly than this one by this President.” One month later, he announced that “the battles of Afghanistan and Iraq have been won decisively and honorably.” Kristol also derided warnings of a Sunni-Shia conflict as “pop sociology” and claimed there was “almost no evidence of that at all. Iraq’s always been very secular.”

The war dragged on, and the Kristol ball remained cloudy. He and coauthor Robert Kagan greeted the first anniversary of the Iraq invasion by announcing that Iraqis “had made enormous strides” toward liberal democracy, smugly deriding prewar predictions “that a liberated Iraq would fracture into feuding clans and unleash a bloodbath.” Nine months later, Kristol judged the Iraqi elections of January 2005 to be “a genuine turning point.” Wrong again: Iraq spiraled ever deeper into sectarian violence in 2006 and 2007, and the bloodbath Kristol had dismissed became a reality.6

This string of failed forecasts flowed directly from the neocons’ naive belief that democracy would be easy to establish and from their ignorance about Iraq and the broader region. These beliefs also made them easy prey for the blandishments of unscrupulous individuals like Iraqi exile Ahmad Chalabi. Because they assumed the occupation would be easy and cheap, they saw no need to prepare for protracted war and dismissed the realists’ warnings that establishing a stable political order would be a long, expensive and uncertain undertaking.

Neoconservatives now proclaim that the “surge” is working and that victory is within reach. Unfortunately, this is not true. There was never any question that the United States could dampen the violence by increasing troop levels. The key issue, however, is whether the surge will enable Iraqis to create a workable political system and an effective military that can disarm powerful local militias. That has not happened, which is why the United States will remain stuck in Iraq for the foreseeable future, trying to prop up a government that still cannot stand on its own.

In any case, the tactical success of the surge hardly vindicates the neoconservatives’ larger strategic blunders. Not only did they get us into a quagmire in Iraq, but their war helped increase Iran’s power in the region. Pro-Iranian leaders now govern in Baghdad, and U.S. threats have given Tehran additional incentives to acquire nuclear weapons. Remarkably, the neocons could hardly have done more to help Iran and hurt the United States had they been on President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s payroll.

But Iraq is hardly the neocons’ only failure.

By marching us into Baghdad while refusing to negotiate seriously with “evil” North Korea, they made it possible for Kim Jong Il to withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty, recycle nuclear material and test a nuclear weapon. Efforts to contain Pyongyang’s program made progress only after Bush abandoned the neocons’ approach to North Korea and engaged in patient diplomacy.

By insisting on elections in the Palestinian territories while impeding any genuine effort toward peace, neoconservatives helped Hamas win a parliamentary majority in 2006 and made a two-state solution that would preserve Israel’s Jewish character even more elusive. The subsequent refusal to recognize Hamas then exposed the hypocrisy of the Bush administration’s alleged commitment to spreading democracy in the Arab world. And by backing Israel’s ill-conceived strategy during the summer 2006 Lebanon war, neoconservatives undermined the pro-Western Siniora government, prolonged a conflict that cost Israeli lives and strengthened Hezbollah. They claim to be committed to Israel’s well-being, but the neoconservatives’ policies have in fact been deeply harmful to the Jewish state.

The neoconservative approach to foreign policy has driven America’s global image to new lows and given millions of people reason to doubt our commitment to the rule of law, justice and basic human rights. And while the United States has floundered, a rising China has quietly expanded its power, prestige and influence.

This record is not simply a run of bad luck; only policy makers committed to a deeply flawed worldview could achieve results so far from their declared objectives. In each case, failure occurred because neoconservatives inflated threats, exaggerated what military force could accomplish, eschewed diplomacy and blithely ignored facts that didn’t fit their preconceived notions.

It is also instructive that one of George Bush’s only foreign-policy successes occurred when he ignored the neocons’ advice. Building on the Clinton administration’s earlier efforts, the Bush team convinced Libya to abandon its WMD programs in 2003. A key step was the decision to forego “regime change” and leave Muammar el-Qaddafi in power. Had Bush listened to the neoconservatives who opposed this compromise, Qaddafi might still have WMD today.

NEOCONSERVATISM’S inadequacy as a guide to policy is no longer debatable: we have run the experiment and the results are in. If a physician misdiagnosed ailments with the regularity that neoconservatives have misread world politics, only patients with a death wish would remain in their care.

Yet politicians like John McCain and media outlets like the New York Times and Washington Post continue to treat neoconservatives as fonts of wisdom, while giving only occasional space to the realists whose track record has been far superior. However disappointing this may be to those who hope for better, realism offers one consolation: a country as powerful as the United States can afford to make lots of mistakes and still survive. But that is small comfort when one contemplates the array of problems the next president will inherit from the neoconservative moment. Until politicians and media organizations consign neoconservatism to the same ash heap reserved for Leninism, Lysenkoism, phrenology and other failed beliefs, anyone who wants a more effective U.S. foreign policy had better get used to disappointment.

Stephen M. Walt is the Robert and Renee Belfer Professor of International Relations at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

1See Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987), chap. 8; Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1979), pp. 179–180; John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Soviets Can’t Win Quickly in Central Europe,” International Security, vol. 7, no. 1 (Summer 1982).

2See Zbigniew Brzezinski, Brent Scowcroft and Richard Murphy, “Differentiated Containment,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 76, no. 3 (May/June 1997).

3See William Wohlforth, “The Stability of a Unipolar World,”International Security, vol. 24, no. 1 (Summer 1999); Stephen M. Walt, Taming American Power: The Global Response to U.S. Primacy(New York: W. W. Norton, 2005).

4See George Bush and Brent Scowcroft, A World Transformed (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), pp. 489.

5See Brent Scowcroft, “Don’t Attack Saddam,” Wall Street Journal, August 15, 2002; John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, “An Unnecessary War,” Foreign Policy, vol. 134 (January/February 2003); Andrew J. Bacevich, “The Nation at War,” Los Angeles Times, March 20, 2003.

6The Iraq Body Count database, which is based on published death reports, estimates that there have been between eighty-five thousand and ninety-two thousand violent deaths since the U.S. invasion in March 2003. Estimates by the Iraqi government, the World Health Organization and others are significantly higher, in some cases well over five hundred thousand dead. The United Nations reports that nearly 5 million Iraqis had fled their homes by 2007, and that 2.5 million Iraqi refugees had left the country.

Muravchik responds:

STEPHEN WALT has converted me to realism. If U.S. containment policy—globe-girdling alliances, overseas bases galore, massive foreign aid, billions spent on ideological warfare—represents “realism”; and if Ronald Reagan’s anti-Communist policies—the hot rhetoric, the Reagan Doctrine, the National Endowment for Democracy, the military and intelligence buildups, Star Wars—represent “realism,” sign me up.

I poke fun at Walt’s methodology: footnotes lend a patina of scholarliness to a coarse and dishonest argument. Thus, he quotes William Kristol’s embarrassing underestimations of the forces required in Iraq, but shamelessly fails to mention that Kristol soon volubly advocated sending more. He professes solicitude for Israel, although the anti-Israel diatribe that made him famous is celebrated among devotees of Israel’s destruction. (Recently a convicted Hamas militant from Chicago entered Walt’s work into his sentencing record to justify his acts.) Walt whines that neocons err unfailingly, realists are consistently prescient, yet the world embraces the former and ignores the latter. Can this be?

Walt flatters himself that realists uniquely see “the world as it reallyis.” But the real world is nuanced, often ambiguous. Walt’s world is stick figures, straw men, parodies, exaggerations. Is Maliki a “pro-Iranian leader”? Yes, but he is also pro-American and he is fighting the pro-Iranian, anti-American Sadrist militias. Is Ahmadinejad truly happy to have U.S. soldiers on his borders? Do neocons really call our enemies a “tightly unified monolith”? If so, why no quote?

Walt appropriates for “realism” any successful policy and attributes to neocons any unsuccessful one, twisting things to fit. He paints containment as a “realist” policy based on George Kennan’s foundational role. The strategy that Walt says “won the cold war” lasted over forty years, and most of that time Kennan lamented what he had wrought, precisely because he was a realist. Moreover, Kennan’s version of containment was not Walt’s. Here’s Kennan: “The adroit and vigilant application of counter-force at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points.” Here’s Walt: “Preventing Moscow from seizing the key centers of industrial power that lay near its borders.” Walt boasts that realists opposed the Vietnam War, which followed from containment. You can’t have it both ways: claiming credit for containment and for opposition to Vietnam.

Were Reagan’s policies “closer to the realist ideal”? In Walt’s caricature Reagan’s main action toward the USSR was selling grain. Then why did TASS, for example, call Reagan a “bellicose lunatic anti-Communis[t]”?

Walt says Qaddafi relinquished his nuclear project due to American renunciation of regime change. I suppose he didn’t notice the invasion of Iraq. Bush’s neocon hard-line, says Walt, caused Pyongyang to renounce the NPT, but it had been violating the NPT for fifteen years and had produced a bomb, per U.S. intelligence, before Bush took office. Walt quotes Edward Luttwak to imply that neocons, unlike realists, opposed the first (good) Gulf War. But what makes Luttwak—whose mantra is that economics trumps politics—a neocon? Actually, neocons supported that war unanimously while realists were divided.

Walt declares the (neocon-inspired) surge a failure and the (realism-inspired) negotiations with Pyongyang a success. But how can he know their outcomes? Because he portrays realists as prescient. The purpose of his footnotes is to bolster that claim although most are vague, sourcing no specific quote.

Walt begins by citing Walt, so I looked it up.

In 1987 he wrote:

The current balance of world power . . . is likely to remain extremely stable.

Oops.

In a 1990 post-cold-war edition, Walt hedged his forecasts but here are some.

Perceptions of U.S.-Japanese rivalry are growing, now that the Soviet threat no longer provides a powerful motive for cooperation.

The Eastern European states may lean toward the West should Soviet intentions appear more threatening, or tilt back toward Moscow if a reunified Germany poses the greater danger.

As for NATO itself, the optimistic rhetoric about maintaining the “Atlantic Community” should be viewed with some skepticism.

Realists, says Walt, know that “all great powers tend to think that spreading their own values will be good for others.” Aside from being erroneous (Hitler thought no such thing), this finally brings us to genuine realism. Is there no difference between spreading Communism and spreading democracy, say, between West Germany and East Germany? Walt caveats that realists are “neither moral relativists nor disinterested in values,” but he neither explains nor supports this claim. Two paragraphs later he notes with satisfaction that America’s withdrawal from Vietnam eventuated in “free markets and normalized relations with Washington,” shedding no tear for the autogenocide of Cambodia and the Vietnamese boat people.

Discounting the dishonest polemics, Walt’s case boils down to the undeniable failures of neocon-supported policy in Iraq. Merely to oppose the war, however, is not enough. America must find a response to the challenge that became vivid on 9/11. To date, realists have offered none.

Walt responds:

JOSHUA MURAVCHIK would have us believe that neoconservatives are just energetic liberal internationalists, even though neoconservatives used to condemn liberals at every opportunity while trumpeting their own unique approach for remaking the world in America’s image. By pretending now that neocons were merely good-old-fashioned Wilsonians, he seeks to claim credit where none is due and to deny responsibility for neoconservatism’s failures.

Muravchik begins by blaming World War II on realism, implying that the war would have been prevented had neoconservatives been in charge. This is silly, neoconservatism did not even exist before World War II. In any case, the interwar period was characterized less by realist policies than by misplaced idealism (remember the Kellogg-Briand Pact?) and it is no accident that one of the classic realist works, E. H. Carr’s Twenty Years’ Crisis (1939), was an incisive critique of idealistic interwar diplomacy.

More importantly, had neoconservatism been around back then, its emphasis on ideological purity would have been a recipe for disaster. The key strategic problem in the 1930s was the presence of several revisionist dictatorships: Germany, Italy, Japan and the Soviet Union. This meant that any serious attempt to stop Hitler required cutting a deal with the even-more murderous Stalin. Presumably, that is a policy no true neoconservative could condone. Instead, neoconservatives would have had America use force to topple all these tyrants and impose democracy, at immeasurable cost. World War II was a tragedy, to be sure, but the policies Muravchik decries allowed the United States to pay a comparatively small price and emerge the world’s dominant power.

Muravchik’s portrayal of the postwar order is equally off base. The true architects of containment were realists who understood that the United States had to take the leading role against the Soviet Union, while recognizing that multilateral institutions like the United Nations and NATO could be useful means to that end. Containment cannot have been of “neocon design,” as Muravchik suggests, because there were no neocons back in 1950. Moreover, those who emerged later—such as Irving Kristol—opposed containment and favored rollback instead. Neoconservatives are also openly skeptical of international institutions and especially contemptuous of NATO. If they had been an influential force after World War II, the alliances that won the cold war might never have been created and World War III would have been more likely.

As expected, Muravchik tries to recruit Ronald Reagan into the neocon pantheon, but his own account contradicts this claim. Muravchik terms America’s support for Iraq during its war with Iran “one of America’s most nakedly realist sallies,” and says it led to the 1991 Gulf War. Has he forgotten that U.S. support for Saddam began under Ronald Reagan? And does Muravchik think it would have been better to let Iran win?

Muravchik concludes by claiming that realism “had virtually nothing to suggest in the face of terrorism” except “breaking America’s friendship with Israel.” Wrong again. After 9/11, realists called for a laserlike focus on al-Qaeda and warned that invading Iraq was a foolish diversion. Realists advocated tough-minded diplomacy toward Iran and Syria and evenhanded engagement in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process as part of a broad effort to undermine Islamic extremists. No realist ever advocated “breaking friendship with Israel”; instead, they prefer to treat Israel as a normal country while opposing its self-destructive effort to colonize the Occupied Territories, an approach that would be better for the United States and Israel alike.1

Neoconservatives had a different answer to 9/11. The result: we are bogged down in Baghdad, the Taliban is back, Osama bin Laden is still at large, Hezbollah and Hamas—not to mention Iran—are more powerful, and Israel is closer to becoming an apartheid state. If you think this is progress, then stick with the neocons.

Finally, Muravchik claims neoconservatives “treat purely moral concerns . . . as a higher priority than would realists,” yet his response evinces little concern for ordinary human beings. He expresses no remorse at the suffering that neoconservative policies have wrought and seems mostly concerned that the neocons are now “taking their lumps” over Iraq. What matters to him is political standing in Washington, not the hundreds of thousands of needless Iraqi deaths, the millions of refugees who fled their homes, or the tens of thousands of patriotic Americans killed or wounded. So let us hear no more about the neoconservatives’ “moral” convictions. Amid such company, the realists who opposed the war can stand tall.

1For realist approaches to the post-9/11 world, see my “Beyond Bin Laden: Reshaping U.S. Foreign Policy,” International Security, vol. 26, no. 3 (Winter 2001/2002); and the bipartisan report of the Iraq Study Group, chaired by James Baker and Lee Hamilton.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Realist Persuasion

When it comes to war and peace, foreign policy ”realists” from Metternich to Kissinger have been seen as cold-blooded, calculating, and amoral. But there’s another realist tradition – a distinctively American one – and it’s time to revive it.

BRENT SCOWCROFT, the ever-loyal and self-effacing national security adviser to President George H. W. Bush, made news late last month in the pages of The New Yorker, venting his profound disenchantment with the foreign policies of his old boss’s son, President George W. Bush. In foreign policy parlance, Scowcroft is known as a ”realist.” According to The New Yorker’s Jeffrey Goldberg, author of the Scowcroft profile, realism is ”the idea that America should be guided by strategic self-interest, and that moral considerations are secondary at best.”

Goldberg is being kind. The charge commonly lodged against realists like Scowcroft is that they disregard moral issues altogether. As a consequence, realism has long since acquired unsavory connotations, not only among liberals keen to alleviate the world’s ills but also among neoconservatives keen to liberate the oppressed. Critics on the left accuse realists of being cramped, callous, and cynical. Those on the right see realism as little more than a pretext for isolationism.

In fact, when it comes to moral issues, realism has gotten a bum rap. As the events of the post-Cold War era have reminded us, idealism-whether the left liberal variant that emphasizes humanitarian interventionism or the neoconservative version that urges using American power to promote American values-provides no escape from the moral pitfalls of statecraft. If anything, it exacerbates them.

Good intentions detached from prudential considerations can easily lead to enormous mischief, both practical and moral. In Somalia, efforts to feed the starving culminated with besieged US forces gunning down women and children. In Kosovo, protecting ethnic Albanians meant collaborating with terrorists and bombing downtown Belgrade. In Iraq, a high-minded crusade to eradicate evil and spread freedom everywhere has yielded torture and prisoner abuse, thousands of noncombatant casualties, and something akin to chaos. Given this do-gooder record of achievement, realism just might deserve a second look.

There is, to be sure, a self-consciously amoral Old World strain of realism, a line running from Metternich to Bismarck in the 19th century and brought to these shores by Henry Kissinger. But there also exists a distinctively American realist tradition that does not disdain moral considerations. This homegrown variant, the handiwork of prominent 20th-century public intellectuals such as the historian Charles Beard, the diplomat George Kennan, the journalist Walter Lippmann, and the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, provides a basis for seriously engaging the moral issues posed by international politics.

For Americans desirous of extricating the United States from the moral swamp into which the Bush administration has wandered, this largely forgotten American realist tradition that Scowcroft (and others) are trying to resurrect just might provide a useful map.

What’s the essence of this tradition? To begin with, realists see politics as a never-ending competition for power. The president of the United States may be the Most Powerful Man in the World, but he can no more change the nature of politics than he can eradicate original sin. As a result, realists view ”world peace” as a chimera. Saving the world is God’s work. The statesman’s obligation is to avoid cataclysm and to place limits on the brutality to which humankind is prone.

Not surprisingly, the realist prizes stability, recognizing that the alternative is likely to be chaos. This does not provide an excuse for inaction and passivity in the face of distant evils. Rather it counsels modesty of purpose and an acute sensitivity to the prospect of unintended consequences. For realists, the notion that globalization (according to Bill Clinton, channeling the neoliberal New York Times columnist Tom Friedman) will produce global harmony or that American assertiveness (according to George W. Bush, channeling Bill Kristol, editor of the neoconservative Weekly Standard) will ”transform” the Greater Middle East is pure folly. Americans, wrote Niebuhr in his book ”The Irony of American History” (1952), fancy themselves to be ”tutors of mankind in its pilgrimage to perfection.” But the human condition does not admit perfection. ”We could bring calamity upon ourselves and the world,” he warned, ”by forgetting that even the most powerful nations…remain themselves creatures as well as creators of the historical process.”

Realists likewise refuse to don rose-colored glasses when considering the United States itself. As a consequence, they understand that ”American exceptionalism” is a snare. Realists reject claims of American innocence-the conviction, as Niebuhr wrote in the same book, that ”our society is so essentially virtuous that only malice could prompt criticism of our actions.”

The United States emerged as the world’s sole superpower not due to its superior virtue but because it prevailed in a bloody century-long competition. Among the principal combatants in that contest were three genuinely odious criminal enterprises: the Third Reich, the Soviet Union, and Mao’s China. The United States came out on top because it allied itself with Stalin against Hitler and subsequently made common cause with Mao against Stalin’s successors. These were not the actions of an innocent nation.

To pretend, as George W. Bush does, that the United States differs from all other powers in history-that it acts apart from calculations of power and self-interest-gives Americans an excuse to avoid thinking seriously about the forces actually motivating US behavior. Realists see that as a particularly dangerous tendency. The role of oil in shaping US policy offers a case in point.

Likewise, realists view warily the claims of ideology. In 1952, Niebuhr, archetype of the anticommunist liberal, observed that the Cold War had summoned the United States to confront ”evils which were distilled from illusions not generically different from our own.” The illusions to which Niebuhr referred grew out of what he called ”dreams of managing history” that flourished on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Senior officials in Washington were no less certain than members of the Soviet Politburo that they had unlocked history’s secrets and could both divine and determine its future course.

Niebuhr would no doubt find it ironic that today the United States once again finds itself pitted against an adversary motivated by ”illusions not generically different from our own.” Al Qaeda’s leaders declare that Allah wills the restoration of the Caliphate and the triumph of Islam everywhere. President Bush declares with equal fervor in his 2002 National Security Strategy that there exists ”a single sustainable model for national success” and that the entire world is destined to embrace democratic capitalism.

The point is not to equate the two views, but to note the extraordinary presumption that underlies each. A realist would counsel against being quite so dogmatic in forecasting history’s purpose. Just possibly-based on the record of the past couple millennia-surprises lie somewhere ahead. ”The paths of progress,” observed Niebuhr, have ”proved to be more devious and unpredictable than the putative managers of history could understand.”

Realists in the American tradition are similarly circumspect when it comes to power. On the one hand, they prize it. On the other hand, they view it is a fragile commodity. The prudent statesman deploys power with great care. These realists appreciate that ”greatness” is transitory. The history of Europe from 1914 to 1945 testifies to the ease with which a few arrogant and short-sighted statesmen can fritter away advantages accumulated over centuries, with horrific consequences.

Determined to husband power, realists cultivate a lively awareness of what power-especially military power-can and cannot do. They agree with Kennan, principal architect of the Cold War strategy of containment, who wrote in his book ”American Diplomacy” (1950), that ”there is no more dangerous delusion…than the concept of total victory.” At times, war becomes unavoidable. But realists advocate using force as a last resort-hence, the dismay with which they view the Bush doctrine of preventive war.

To the extent war can be purposeful, realists see its utility as almost entirely negative. War is death and destruction. Politically, it can reduce, quell, eliminate, or intimidate. But to wage war in order to spread democracy, as President Bush says the United States is doing in Iraq, makes about as much sense as starting a forest fire to build a village: It only gets you so far, and the costs tend to be exorbitant.

Costs matter because resources are finite. In the formulation of foreign policy, realists emphasize the importance of ”solvency.” Lippmann, who in maturity abandoned the Wilsonian views of his youth to advocate realism, gave particular weight to this theme. This means ensuring that a nation’s commitments don’t outstrip its resources.

Were he alive today, Lippmann would surely see the present administration as hellbent on bankruptcy. President Bush declared an open-ended war on terror without bothering to mobilize the nation or even to expand the size of the armed forces. Instead, he cut taxes and urged us to take a vacation. The consequence: red ink, growing indebtedness to the rest of the world, a badly overstretched military, and assurances that all will come out well in the end. Realists have their doubts.

When policies go awry-as Mr. Bush’s Iraqi adventure surely has-realists resist the tendency to look for scapegoats. In the midst of ”Plamegate,” the inclination is to blame the Iraq debacle on White House officials whose alleged lies enabled the president to put one over on an unsuspecting people.

Realists are not so willing to let the citizens of a democracy off the hook. In his ”Devil Theory of War,” propounded in the late 1930s, Charles Beard derided the commonly held view attributing the American penchant for war to the machinations of some conspiracy or cabal. ”War is not the work of a demon,” wrote Beard. ”It is our very own work, for which we prepare, wittingly or not, in ways of peace.”

The Iraq War of 2003 didn’t come out of nowhere; it represents the culmination of misguided policies, virtually all of them-including the 1980s ”tilt” toward Saddam Hussein-carried out in plain sight of the American public. Blaming everything on Bush won’t prevent a recurrence of Bush’s mistakes. A realist might suggest that Americans looking for someone to hold accountable begin by looking in the mirror.

Andrew J. Bacevich is a professor of international relations at Boston University and is the author of ”The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War” (2005)![]()

Frankly I Like Newt’s Thoughts on Illegal Aliens « The NeoConservative Christian Right said,

December 3, 2011 at 7:12 pm

[…] minded Ron Paul – wow is that guy out of sync with the meaning of American Exceptionalism and American National Interests or […]

Liberty Requires A Leap Of Faith, Strength With Humility. | Freedom to Fascism said,

December 18, 2011 at 8:43 pm

[…] Liberty is not a mindset of force. (here, here, here and here). […]

My Homepage said,

May 18, 2012 at 7:56 pm

… [Trackback]…

[…] Read More here: westphalianpost.wordpress.com/machtpolitik/ […]…

Ben Wilson said,

May 6, 2016 at 5:04 am

An important factor in IR is “power” or “relative power with other countries”. That is a fundamental factor in any equation. Ex: Prof Muravchik talked about the period between WW1 and WW2 that the world would have been better under Wilson idealism (or in modern terms “neocon” approach). However, the US at the time was not yet the dominant or hegemonic power. While some of the European powers were on a decline, but they were nevertheless formidable. The world was not unipolar or even bipolar. In such an international system, it would be extremely difficult to effectively implement a US driven idealism approach to world affairs.