Of Westphalia and Appomattox

Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy and David Cameron have all declared multiculturalism a failure. Berlin, Paris and London all realise that in the continent where nationalism was born, the harmonious melding of cultures is not achievable.

In Europe and much of the old world, History has served the purpose of separating cultures. Europe especially, due to its geography, has been a perfect case of identity politics trumping any ideology. It was in Europe afterall that nationalism was born. Unlike what many believe, nationalism was not born in the XIX century. Identity politics had been an integral part of the Scottish rebellions, the German reformation and countless other phenomena prior to the modern era. Modernity codified these trends but it did not inaugurate them.

The ultra-nationalism of the XX century was short lived, yes, but this trend was extreme and in many ways self-consuming. The reaction to ultra-nationalism however has been equally extreme, being characterised by universalism, radical individualism and pacifism at any cost. This recipe is beginning to crumble since the European Union is now more than ever a project in distress. Those who dread disintegration claim more integration is the only alternative but this does not stand to reason: if integration was the answer Europe would not be in distress after having begun political on top of economic integration. What could Euro-bonds and ECB fiscal controls do to prevent dissimilar productivity in the different European states? Monetary and financial engineering cannot prevent radically different work ethics and civic mentality. The Greeks will not become more individualistic anymore than Finns will become more collectivist – barring any totalitarian social engineering practices of course.

Instead of uniformity, the only enduring reality in Europe is that of disunity and dissimilarity, however close the civilisational contacts may be. The Treaties of Westphalia epitomised as much by bringing the concept of sovereignty into current use. European sovereignty though can only exist through ethnic homogeneity and the subalternation of the normative. This was the political translation of the end of the Thirty Years War which saw the crystallisation of multipolarism in Europe. After Rome and the Franks, the Habsburgs had been the third polity to vie for continental domination and fail. At the same time, Europe being the smallest continent had allowed for cross-cultural interaction to an extent whereupon the different peoples shared a common cultural legacy. Westphalia was thus the codification of ethnic separation (proto-nationalism) with normative consensus (Christianity). The respublica christiana was politically disunited but ideologically cohesive – with theological divides often serving only to make salient the ethnic fault lines (Catholicism/Presbyterianism in Scotland, Catholicism, Islam or Orthodoxy in the Balkans, etc).

Among the necessary consequences of the Westphalian system in Europe (especially Western Europe) has been xenophobia but also internationalism. It is inevitable that stark frontiers and centralized states will invariably lead to cooperation: European states are small and multipolarism requires geostrategic variable geometry. On the other hand, in a hermetic ethnic monopoly, minorities will invariably find it hard to integrate as Jews and Gypsies would attest. Both these tendencies are perhaps better observed in simplistic regime types of the totalitarian tradition, namely with both communism and fascism.

American Colonization Society ship the Elizabeth sets sail to what was to become Liberia, a colony of American slaves in Africa and today known as a failed state.

In Asia multicultural empires have rather been the norm, with eastern Europe and the Balkans corresponding to some standard somewhere in between western European nation-states and Asian multi-ethnic empires. This is why sovereign borders are notoriously difficult to create in the Middle East but multi-ethnic harmony comes naturally (Istanbul, Jerusalem and Baghdad or Persia, Asia Minor and Mesopotamia being good historical examples). The artificial emulation of western state apparatuses in the Middle East leads to necessary ethnic tensions given that within a small state, unlike within an empire, ethnic identity is crucial to the monopoly on legitimate violence. Empires demand at most an ethnic core but due to their extension it would make little sense to fear one or another minority.

The colonisation of the Americas originated a peculiar misfit: the settlers were European but the territory did not lend itself to European style nation-states. Quite to the contrary, America’s near absence of major topographical barriers and the mixed nature of its settlers favoured an Asian type polity formation. The initial immigration was largely comprised of Europeans which meant that integration was easier given it was intra-civilisational. African slaves, Hispanic-Americans or Asian migrants either did not possess citizenship or were too small in number to be of consequence. The system endured and prospered until the War of Secession when apart from all the economic tensions between North and South, national identity was propelled by abolitionists as a fracturing issue.

Now, unlike what the founding fathers had intended, economic and political liberalism was beginning to spillover to society at large and the fundamental incompatibility of liberalism with raison d’état began. To be clear, America was only a multicultural society so long as it remained a European anglophone republic in its core. The next question then should be whether the US could have afforded to remain a slaver state: it doesn’t seem very likely given the incompatibility with liberalism. However, the rejection of domestic slavery is a very different proposition from the promotion of individual freedom abroad, from the automatic granting of citizenship to millions of the illiterate and economically disenfranchised overnight, and finally from forceful universality of the abolition.

Other societies have evolved very differently and cannot require the same cultural and political solutions as the anglophone ‘new world’. Citizenship is not equivalent to nationhood and ultra-inclusiveness risks cohesion – one wonders what would have happened if Spartans had granted Helots their freedom as well as full citizenship rights in Laconia… Finally if abolition was indeed a social concern of the American people, why not simply allow each state to approve it in their own timing – surely there was no doubt such a path was unidirectional?…

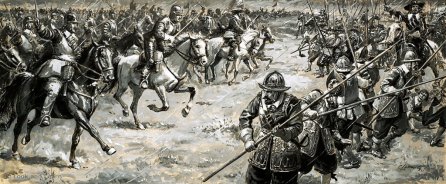

The Confederacy’s decision to press for independence was a dramatic one but not illogical. The South was betting on a North American Westphalia. They had the precedent of Yorktown (1783) – continental secession from the British empire – and they had the sympathy of overseas powers as well as Native Americans. This could have meant a partition of north America and a multiple state balance of power in the long run. As Grant would come to prove however, North America is not Europe: Appalachia cannot be ruled by more than one power and the Atlantic ocean is too large to allow European polities to project much force into America. Topographical and geographical obstacles made the Habsburg quest to control central Europe too much of a logistical challenge: the ‘Spanish road’ was vulnerable (i.e. Palatinate), the western approaches and the English channel too risky (Spanish Armada), all this even with the advantage of superior numbers as well as tactics; the North Sea and Baltic polities always free to project uninterrupted influence over continental Europe. Conversely, the battlefields of Maryland and Virginia were almost always chosen by generals rather than imposed by geography, armies were free to roam around the great plains of the Midwest and rivers proved to be avenues for troops rather than natural defences against them. Unlike Europe, America cannot be divided from within and is too far to be divided from without.

Therefore, the significance of Appomattox was the very opposite of Westphalia: like Worms in 1122, Appomattox in 1865 meant that normative power bests temporal power, ideological identity trumps cultural identity. Above all, the extremism of abolitionists lay in them being constitutional fundamentalists – which the same founding fathers who signed a peace treaty that saw the need for all the Dunmore Proclamation black freedmen to be exiled, were not. Some might say ‘so much the better!’ since that allowed for the liberation of the slaves but it did also sow the seeds of systemic dysfunction for forthwith the question of identity would be one resolved by the supremacy of beliefs over ethnicity, values over interests, ideology over identity. As the last US election of 2012 proved though, the interests of minorities (loose immigration laws) trump their ideological background (Catholic, Methodist, Southern Baptist conservatism) as it trumps in almost every polity. The inconsistency then is that of identity: if minorities vote according to their ethnic identity rather than according to their ideological identity, how can they then be American?

English-Americans or German-Americans do not rush to defend Britain or Germany whenever these nations disagree with the US or when their brethren have disputes with the Federal government on national soil but contemporary minorities do the opposite. Worse still, unlike Italians and Irish whose integration was already made difficult due to their non-compliance with the WASP standard, Hispanics and African-Americans do not even originate from the same civilisational setting as European America – Hispanics have European roots but also Amerindian and African ones.

(Perhaps this reality helps explain how easily the US find themselves involved in the causes of minorities around the world from Jews or Armenians to Albanians)

The imagery of Monrovia and Liberia is a profoundly ironic one since the same historians who so readily admit the enterprise of resettling American slaves in Africa was a failure, have scarcely a word of doubt about the success of their adaptation to anglophone North America.